Want to be part of unique career conversations?

Signup now to start exploring fresh perspectives from The Ken’s community

The demise of conventional careers is not an exaggeration. Fewer people entering the workforce today will have careers where they move straight up a ladder for three to four decades, following a neat path laid out for them even before they left university.

Anyone who’s working today will need to build their own careers over time, not climbing rungs but moving along the edges of a lattice. It’s a route that is difficult to plan for, but allows anyone who is ambitious enough to seize opportunities in ways that few professionals did before.

3 Speakers

Each speaker with a diverse set of knowledge and expertise

A career lattice is a framework that brings together lateral experiences, adjacent skills, and peer networking to move individuals into any position they are qualified for. The ability to make lattice-like moves is now an essential skill.

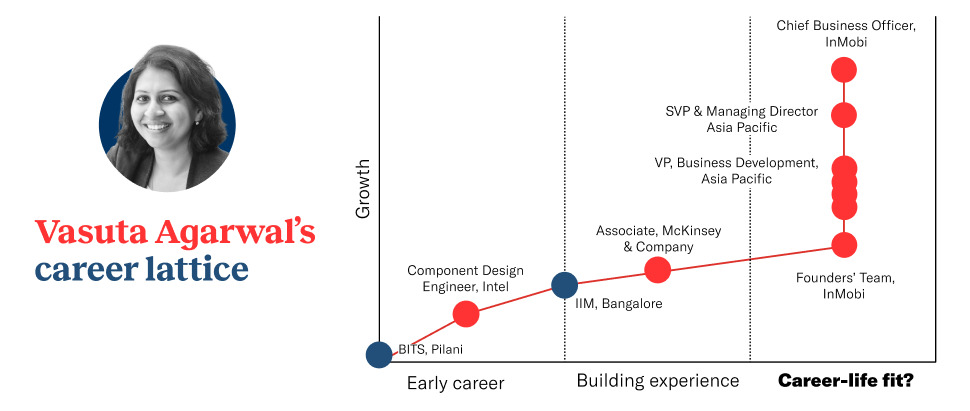

The Ken held a discussion on career lattices with Harshil Mathur, CEO and co-founder of Razorpay; Vasuta Agarwal, chief business officer of InMobi; and Prof. Sourav Mukherji of IIM Bangalore on 19 May 2025. The panel covered a wide range of themes, including what they personally gave up while exploring new ways of building their careers, how to seize unconventional opportunities in the workplace, and practical advice for people in all phases of their professional lives.

We invite you to continue the conversation.

Trade-offs

Moving from one role to another can unlock unexpected opportunities, but it also carries a cost, whether in the form of lost income or tolls on one’s time. This manifests in different ways for each person. Knowing how to give up something in order to generate outsized gains is an important part of making a lateral career move.

Q 1. What’s the biggest trade-off that you’ve had to make while making a jump in your career lattice? And why did you do it?

What you love vs. what you're great at

It's common advice to find the intersection of what one is passionate about and what one is good at doing. But many get stuck—pursue something that one loves and get better at it over time, or learn to love the work that one is good at? There’s no easy answer.

Q 2. How do you find the intersection of what you love doing and what you’re good at doing?

Sourav Mukherji Guest Speaker

It’s an iterative process. Soon enough, in a very happy, coincidental situation, you will find that you are good at something and that you love doing it. To mention the concept of ikigai, there are two other things: the world thinks that what you do is useful, and that somebody will pay you for it. But you may not satisfy all four conditions when you are starting your career, or depending on what your situation in life is. When I started my career, I was certainly not doing something that I loved, but I adjusted over a period of time and thought about how I can move towards something else. People very often realise that what you are good at is also something that you love doing. It happens for most of us. You will not get all of what you want on day one, but don't get frustrated, and in the medium to longer run, you will get there. View more responses

Q 3. Can the notion of “doing what you love” change over time?

Harshil Mathur Guest Speaker

Yes. I had zero exposure to finance before I started Razorpay. I had no idea how banks work. I can say clearly that I didn’t have a passion for finance when I started Razorpay. Instead, I had a passion for coding, while the world expected me to work in finance. So, I think what you’re good at vs. what the world expects you to do vs. what you get paid for vs. what you love doing can be very different. Look at Razorpay: our differentiator is not that we are better at managing money; it is that we build the best tech for managing money. So it’s not important for me to be the best at finance; it’s the most important for me to be good at building our product and tech. Now, apply that to careers. You can’t start with what you love. You start with what you’re good at. If you can use what you love as a differentiator, then that’s the best outcome, but that isn’t possible in every role. Now, I don’t code at all—I don’t do what I’m good at—but I still love thinking about product and tech. I spend my time thinking about what’s next for Razorpay, what do we build next? The product and tech is still the core of what I love, but I also have to do all the other things that I can’t say that I love. View more responses

Going deep vs. going broad

One of the big career choices that nearly everyone must make is whether to become a specialist or a generalist. A lattice career demands both—depth for credibility and breadth for adaptability.

Q 4. What should new members of the workforce do in the first 5–10 years after they graduate to increase their chances of developing longer, more fulfilling careers in fields that they’re passionate about? How can they find that?

Sourav Mukherji Guest Speaker

Let me roll back and think about what happened to me when I was young. That was last century. For most of us, our first few jobs or even our profession was not our choice. It was a societal choice. It was a parent's choice. You go to college. If you go to a reputed college, your job will also be okay, and then you are on that treadmill. In the first few years, you have to figure out whether that is what you need to do or what you are good at, and whether you would enjoy it for the rest of your life. Because that’s the time when you are gradually getting control of your life. You are becoming financially independent. You are making choices about your partner. But you also have to find something else that you think you are good at. Find out what your core skill is, what competency that you want to build, and the degree of confidence that that's what you really want in life. At the same time, if you’re in your 20s, it’s fine to not have all the answers. Just show some direction and have the intellectual honesty to tell yourself what you’re good at and what you’re not good at. View more responses

Harshil Mathur Guest Speaker

Co-founder and CEO, Razorpay

The biggest trade-off for me was leaving a job. When I joined Schlumberger, it was one of the highest paying jobs for IIT grads. But one day into that job, I realised that it isn’t for me. When I told my parents that I wanted to leave, there were lots of discussions, and the salary that comes with a high-paying job is addictive. Despite this, I also knew that the tech ecosystem moves fast. So if I stayed at the job for three years, I’d become obsolete. I remember having a conversation with my dad, and it was simply that I felt that I could always find another job, but I didn’t think I could cofound a business if I became obsolete. It would only become harder and harder to build my business. View more responses